Trong thị trường cá cược nói chung, đặc biệt là trong lĩnh vực game Xóc Đĩa Online nói riêng đã xuất hiện rất nhiều nhà cái chủ trì. Điều này vô tình khiến việc chọn lựa một nhà cái uy tín để tham gia cá cược trở nên không hề dễ dàng. Bài viết dưới đây sẽ tổng hợp danh sách những nhà cái uy tín mà chúng tôi đã trải nghiệm cũng như xác minh về độ tin cậy, để bạn đọc có thể tham khảo

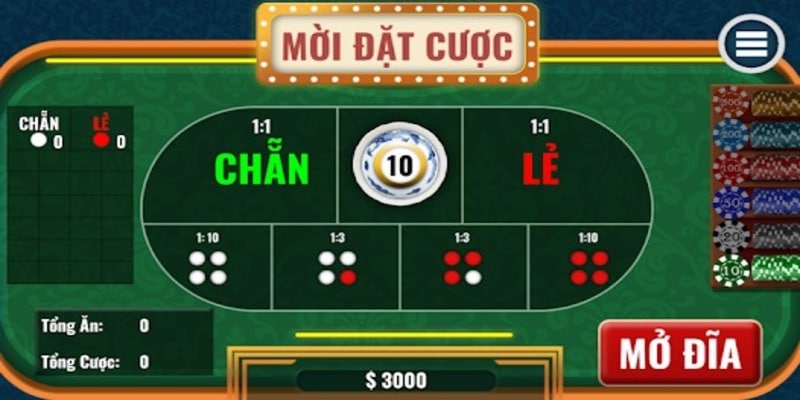

Xóc Đĩa Online là gì? Xóc Đĩa Online chính là phiên bản chơi Xóc Đĩa truyền thống nhưng thông qua mạng internet. Để tham gia trò chơi này, người chơi cần đăng ký một tài khoản cá cược tại một nhà cái có uy tín. Tiếp theo, bạn có thể nạp tiền vào tài khoản rồi bắt đầu tham gia chơi Xóc Đĩa trực tuyến một cách dễ dàng, tiện lợi.

Xóc Đĩa đã trở thành một trò cá cược phổ biến từ lâu trên thị trường Việt Nam và trên toàn cầu. Trong trò chơi Xóc Đĩa Online, người chơi dự đoán kết quả của việc lắc 4 đồng xu có hai màu sắc, trắng và đỏ.

Sự chính xác trong dự đoán kèo cược sẽ quyết định được mức tiền thưởng mà người chơi có thể nhận được, với những dự đoán chính xác sẽ mang lại phần thưởng cao hơn.

Đến thời điểm này, với sự tiến bộ không ngừng của công nghệ cùng sự ưa chuộng của một lượng lớn người chơi, các phương thức đặt cược xung quanh trò chơi Xóc Đĩa này đã trải qua sự nâng cấp đáng kể. Việc này mang lại cho bạn một loạt các cơ hội nhận thưởng dễ dàng hơn với sự đa dạng lựa chọn ngày càng phong phú hơn.

Do sự gia tăng đáng kể của nhu cầu chơi trò chơi trực tuyến, các nhà cái hiện nay cung cấp nhiều lựa chọn cho trò chơi Xóc Đĩa Online có thưởng. Tuy nhiên, không phải tất cả các nền tảng đều thuộc dạng đáng tin cậy.

Nếu bạn không thận trọng trong quy trình chọn lựa nhà cái, nguy cơ rủi ro có thể tác động mạnh mẽ đến tài chính lẫn về cuộc sống cá nhân của bạn thông qua dữ liệu mà bạn đã cấp cho họ. Dưới đây là 8 gợi ý để bạn chọn lựa một cách tự tin mà không lo ngại về khả năng lừa đảo.

K9WIN đang dẫn đầu trong danh sách các nền tảng đổi thưởng uy tín được đề cử. Nơi đây cung cấp một loạt các sảnh trò chơi phong phú, với nhiều biến thể Xóc Đĩa khác nhau, mang lại cho người chơi sự lựa chọn đa dạng.

Ưu điểm – Nhược Điểm

Ưu điểm | Nhược điểm |

Hoạt động kinh doanh cùng với các trò chơi Xóc Đĩa Online được chứng nhận bởi Curacao Gaming. | Việc rút tiền có thể gặp một số khó khăn vì đòi hỏi người chơi phải xác minh tài khoản để thực hiện rút tiền nhiều lần. |

Mức đặt cược linh hoạt. |

BK8 luôn là một trong những cổng game hàng đầu mà bất kỳ người yêu thích trò chơi Xóc Đĩa nào cũng nên trải nghiệm.

Ưu điểm – Nhược Điểm

Ưu điểm | Nhược điểm |

Sảnh cược Xóc Đĩa được cung cấp bởi các nhà cung cấp uy tín như Bbin, SA, AE, SexyGaming… | Các ưu đãi thường đi kèm với những điều khoản ràng buộc khá nghiêm ngặt. |

Dễ dàng tải ứng dụng. |

Không thể không nhắc đến Me88 khi nói đến các nhà cái đổi thưởng uy tín về trò chơi Xóc Đĩa Online. Với đa dạng các sảnh cược casino, Me88 đem lại cho người chơi một trải nghiệm độc đáo nhất.

Ưu điểm – Nhược Điểm

Ưu điểm | Nhược điểm |

Danh sách trò chơi Xóc Đĩa được lựa chọn kỹ càng. | Các chương trình khuyến mãi tại đây thật sự chưa quá đa dạng. |

Hỗ trợ nhiều ngôn ngữ. | Giao diện hiện tại là giao diện chưa hỗ trợ thêm tiếng Anh. |

Với đa dạng các phòng chơi đặc biệt dành riêng cho trò chơi Xóc Đĩa, Fi88 không chỉ là một trong những địa điểm cá cược nổi tiếng mà còn là điểm đến hàng đầu mà người chơi không nên bỏ lỡ.

Ưu điểm – Nhược Điểm

Ưu điểm | Nhược điểm |

Hỗ trợ tài khoản chơi thử. | Hạn chế trong việc hỗ trợ nhiều phương thức thanh toán. |

Tích hợp tính năng đặt cược thông minh cùng với giao diện dễ sử dụng. |

Không có trang cá cược nào có thể cung cấp một loạt các ván đấu Xóc Đĩa Online phong phú với giới hạn cược linh hoạt như Vnloto. Với sự kết hợp của các trò chơi đa dạng cùng giao diện chuyên nghiệp, người chơi sẽ ngay lập tức có được ấn tượng mạnh mẽ từ hệ thống này ngay từ lần tham gia đầu tiên.

Ưu điểm – Nhược Điểm

Ưu điểm | Nhược điểm |

Giao diện bàn chơi được thiết kế hiện đại, tối ưu hóa các tính năng. | Hỗ trợ trực tuyến hạn chế. |

Sảnh chơi đã được cung cấp bởi các nhà sản xuất game hàng đầu như Evolution, Palazzo… |

Để tận hưởng trải nghiệm đầy đủ cũng như an toàn với trò chơi Xóc Đĩa, FB88 được đánh giá cao là một điểm đến không thể bỏ lỡ.

Ưu điểm – Nhược Điểm

Ưu điểm | Nhược điểm |

Đa dạng các sảnh Xóc Đĩa quốc tế, chuyên nghiệp và đầy tiện ích từ các nhà cung cấp như Microgaming, Ebet, Skywind,… | Hạn mức rút tiền hàng ngày tại sân chơi FB88 khá thấp.. |

Trò chơi Xóc Đĩa đổi tiền thật được tổ chức công khai với hệ thống trả thưởng minh bạch. | Không hỗ trợ tốt việc nạp tiền qua cổng thanh toán bên thứ ba. |

VN88 không chỉ là một trong những nền tảng Xóc Đĩa được yêu thích nhất trên thị trường mà còn là một đơn vị hoạt động với sự chính quy bởi được giám sát chặt chẽ bởi tổ chức PAGCOR.

Ưu điểm – Nhược Điểm

Ưu điểm | Nhược điểm |

Phiên bản Xóc Đĩa truyền thống mang lại sự kịch tính cao. | Thường xuyên gặp tình trạng tắc nghẽn cũng như lỗi link truy cập trong các khung giờ quan trọng. |

Bàn chơi 3D hoặc Xóc Đĩa Online với người thật đều đảm bảo được tính minh bạch | Số lượng quảng cáo, banner trong mỗi phiên chơi đôi khi khá nhiều, gây phiền toái |

Nhà cái W88 trong lĩnh vực trò chơi Xóc Đĩa không chỉ là một cái tên tiên phong mà còn là một điểm đến đầu tiên mở ra cánh cửa cho thị trường Châu Á và Việt Nam. Không chỉ vậy, trải nghiệm đánh Xóc Đĩa tại đây còn đem lại cho người chơi những sảnh chơi chất lượng, được đánh giá cao từ những nhà phát hành game nổi tiếng nhất trên toàn cầu.

Ưu điểm – Nhược Điểm

Ưu điểm | Nhược điểm |

Giao diện được thiết kế tinh tế với sự kết hợp hài hòa giữa hình ảnh, màu sắc lẫn âm thanh. | Vẫn chưa tối ưu lắm nêu so sánh từng game với nhau. |

Giao dịch nạp – rút tiền tại đây đều được thực hiện một cách nhanh chóng, minh bạch. | Khi cần hỗ trợ, việc kết nối cũng như chờ đợi nhân viên hỗ trợ tốn điều thời gian đáng kể |

Trong thời gian gần đây, sự phát triển của nhu cầu tham gia các trò chơi trực tuyến, đặc biệt là trò chơi Xóc Đĩa Online, đã trở nên ngày càng đáng kể. Tình hình này dẫn đến sự gia tăng đáng kể của các trang web cung cấp dịch vụ này. Mặc dù điều này mở ra nhiều sự lựa chọn cho người chơi, song nó cũng tạo ra một thách thức mới trong việc chọn lựa trang web Xóc Đĩa có uy tín nhất.

Một trong những yếu tố hàng đầu là sự sở hữu giấy phép kinh doanh hợp pháp. Một trang web chơi Xóc Đĩa Online đáng tin cậy sẽ có giấy phép hoạt động được công bố một cách minh bạch cũng đi kèm với thông tin đầy đủ về nguồn gốc của nhà cung cấp dịch vụ. Giấy phép này thường được cấp bởi các cơ quan hoặc tổ chức có thẩm quyền trong lĩnh vực hoạt động của các sòng bạc trực tuyến.

Tỷ lệ trả thưởng là một yếu tố mà đa số người chơi quan tâm vì thường được xem là một chỉ số quan trọng để đánh giá tính đáng tin cậy của một trang web chơi Xóc Đĩa trực tuyến.

Tuy nhiên, những trang web Xóc Đĩa đáng tin cậy thường có tỷ lệ thanh toán hợp lý, cạnh tranh. Với cùng một số tiền đặt cược, nếu có một nơi nào đó cung cấp tỷ lệ lợi nhuận cao hơn, thì đó chắc chắn là một lựa chọn đúng đắn, phải không?

Khi đánh giá độ uy tín của các nhà cái Xóc Đĩa Online, tốc độ thanh toán tiền thưởng sau khi người chơi thắng cược cùng độ dễ dàng khi người chơi muốn rút tiền thắng cược là một yếu tố quan trọng cần được xem xét.

Tất cả các nhà cái trực tuyến đều yêu cầu người chơi nạp tiền vào tài khoản để tham gia cá cược. Do đó, khi người chơi chiến thắng, các nhà cái cũng phải đảm bảo rằng quy trình rút tiền diễn ra nhanh chóng nhất.

Vào năm 2024, việc tham gia cá cược trực tuyến và chơi Xóc Đĩa trên điện thoại di động đã trở thành một trào lưu phổ biến trên thị trường. Với chỉ vài thao tác đơn giản, họ có thể đăng nhập vào tài khoản để tham gia chơi Xóc Đĩa trực tuyến mọi lúc, mọi nơi.

Vì những lí do này, ứng dụng di động đã trở thành một tiêu chí quan trọng trong việc đánh giá độ uy tín của một trang web chơi Xóc Đĩa Online chất lượng. Tiêu chí này cũng nhằm đánh giá khả năng của nhà cái trong việc phát triển sản phẩm để đáp ứng nhu cầu ngày càng tăng của người chơi.

Trên đây là tất cả thông tin mà chúng tôi muốn chia sẻ về top 8 trang Xóc Đĩa Online đổi thưởng uy tín nhất năm 2024 cùng với những hướng dẫn về việc lựa chọn một nhà cái đáng tin cậy. Mỗi nhà cái đều có các ưu nhược điểm riêng, nhưng dựa trên kinh nghiệm cá cược của chúng tôi, chúng tôi tin rằng thông tin này sẽ giúp bạn có được sự lựa chọn hợp lý nhất.